To disregard the problems facing the Earth and to proceed with business as usual in education would be a betrayal of trust. Our students want to know how to make a difference. They need hope. And it won’t come if all we can offer is another scientific theory or technological fix. We must expand our vision to seek non-scientific alternatives. To make a difference, we must search for different understandings. Let us look to the wisdom of our ancestors. They believed that intelligence is not restricted to humans but is possessed by all creatures – plants as well as animals — and by the Earth itself.

They also believed in spirits. Human welfare was understood to depend on tapping into these wellsprings of wisdom, and all ancient societies (just like indigenous peoples today) had specialists skilled in communication with the natural world and with spirits. These people we now call shamans, and this article argues for the inclusion of shamanic practice in the educational curriculum.

Shamanism gives working access to an alternative technique of acquiring knowledge. Although a pragmatic, time-tested system, it makes no claim to be science. Its strengths and limitations are different from those of the sciences and thus complement them. Being affective and subjective, shamanism offers another way of knowing.

Reason sets the boundaries far too narrowly for us, and would have us accept only the known – and that too with limitations – and live in a known framework, just as if we were sure how far life actually extends. .The more the critical reason dominates, the more impoverished life becomes. Overvalued reason has this in common with political absolutism: under its dominion the individual is pauperised. – Carl Jung

Of course science will offer some valuable new directions, but at the same time we must expand our vision to seek non-scientific alternatives. To make a difference, we must search for different understandings. I am fortunate to live in a country, New Zealand, where many of my compatriots have an understanding of past and future that is fundamentally different from the prevailing ‘Western’ view. Most in our civilisation consider it self-evident that we stand facing the future with the past behind us, but traditionally for New Zealand Maori it is the future that is behind them.

They stand facing the past and their ancestors, who are a living presence in spirit. It is the vision of the ancestors that guides the present generation into the unseen future, with one clear and overriding purpose: to prosper the generations yet to be born.

Nga wa o mua “The days of the past to which we are coming.” — Maori proverb

Let us take our cue from Maori and consider the vision of our own ancestors. No matter what our ethnic background, we will discover that our ancestors (except some of the most recent) believed, like Maori, in the existence of spirits. They also stood in awe of the rich diversity of life forms, and they believed there is mutual interdependency between these forms, humans included, given that everything that exists is alive and conscious. They were of the opinion that intelligence is not restricted to humans but is possessed by all creatures – plants as well as animals — and, for that matter, by the Earth itself. Rock, soil, stream, ocean, wind, air, sky, the stars – all are imbued with consciousness.

Recognising that the Earth and many of its creatures vastly predate humanity and are therefore possessed of much older wisdom, our forebears honoured selected landforms, trees, plants, and animals as their ancestors. They understood that there is deep wisdom in the rhythms of the Earth and an infinite variety of life experience stored by our fellow creatures and by spirits. Human health and welfare were understood to depend on tapping into this wellspring of wisdom. On a planet that is everywhere alive, conscious and inspirited, humans were believed to have many wise allies for counsel and aid.

What is the relevance of this to our current concern about the fate of the Earth? If the ‘star billing’ given by us moderns to our species is unwarranted – if sapiens (wisdom) is not exclusive to homo (humanity) – then could it be that the fate of the Earth is not exclusively or even primarily in our hands?

By our ancestors’ measure, we have grossly exaggerated our self-importance in the intricate web of life. Is it not conceivable that among our intelligent companions on this whirling voyage through space are some who may be capable of restoring the balance we humans have disturbed, of undoing the damage we have wrought? Possibly there are many more shoulders sharing this burden than we think.

Some of the strongest of those shoulders may be the smallest, as was demonstrated dramatically in the aftermath of the 2010 Gulf of Mexico oil well explosion. As millions of barrels of oil poured unchecked into the ocean from the uncapped well, there was a scramble to devise human technologies that would mitigate an environmental disaster of colossal scope.

It took months before the flow was stopped, but in the meantime it was discovered that petroleum-eating bacteria had flourished in the oil plume and contained a vast amount of it. The micro-organisms had not only multiplied at an astounding rate, they also had ramped up their own internal metabolism to digest the oil efficiently. They formed a natural clean-up crew capable of reducing the amount of oil in the undersea plume by half every three days.

We may take hope from the fact that this kind of help is available, but we must also start paying attention, as did our ancestors, to what our travelling companions have to say to us. Every ancient society developed communication with the natural world and with spirits, and they had specialists skilled in the techniques of that communication.

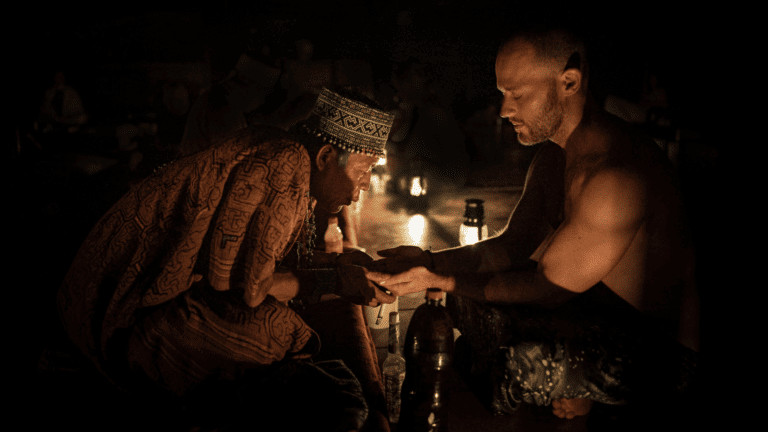

These women and men were held in high regard, but they were approached with trepidation, because they were perceived to be communing with mysterious and awesome forces. In Old French they were called “sorcier,” those in touch with the “Source.” The Anglo-Saxons spoke of the “Ways of Wyrd” known to “wizards” and “witches.”

Shamanism is the term now applied to what has come to be recognised as a worldwide phenomenon, whose practice can be found as far back as we can go in human history. Given the association in the popular imagination of the term shamanism with ‘native, tribal’ cultures, it will come as a surprise to many to learn that their own ancestors practiced shamanism. We are all descendants of shamanic peoples.

Research over the past 150 years by scholars of comparative religion, pre-history and anthropology has revealed strikingly close similarities in the shamanic techniques employed in ancient cultures and in modern indigenous societies worldwide. The word shaman is borrowed from one of those contemporary indigenous societies, the Tungus of Siberia.

We are fortunate there are native shamans still at work, despite the sustained, and in many cases brutal, efforts of colonial governments, Christian churches, and medical authorities to suppress them. In the past forty years there has also been a Western revival of shamanic practice inspired by indigenous teachers and reinforced by the recognition that these ancient spiritual traditions are our shared inheritance.